The promise and peril of deep-sea mining

by Dona Bertarelli

A hidden frontier worth protecting

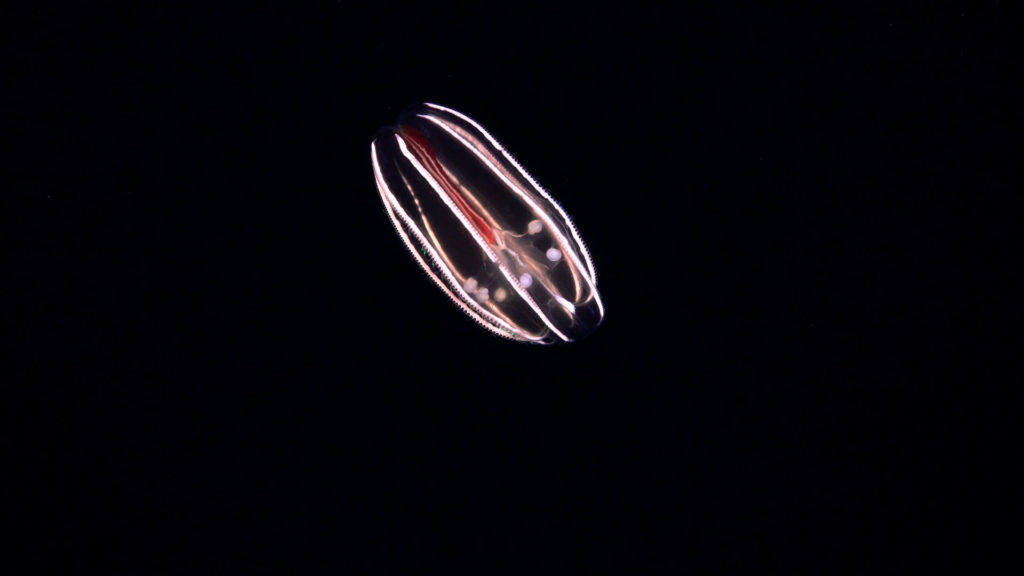

The ocean has always been a source of wonder and purpose in my life. As a sailor, a philanthropist and an advocate I’ve witnessed its vastness, its power, and also its vulnerability. Yet the part of the ocean that perhaps moves me the most is the one we rarely see: the deep. A realm beyond 200 meters, where sunlight cannot penetrate, it covers about half our planet, and hosts life forms more fantastic than anything on land.

These deep-sea inhabitants include bioluminescent fish like the Barreleye, whose transparent head and tubular eyes enable a unique, nearly panoramic field of vision, and the elusive deep-sea Anglerfish, whose glowing lure attracts prey in the pitch-black depths. Many of these species have hardly been studied, and there is still so much more to discover as scientists estimate that less than 1% of the deep seabed has been studied in ecological detail1.

In short, this is Earth’s largest and most diverse biome. It is ancient, fragile, and largely unexplored. Yet it is increasingly under threat.

📷 MBARI (Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute)

Why the interest in deep-sea mining today?

One of the most extraordinary features of this remote environment is the presence of polymetallic nodules, hand-sized, coal-like formations scattered across the seafloor, particularly abundant in regions like the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Pacific Ocean. These nodules are made from metals such as cobalt, nickel, manganese and copper currently used in some types of batteries and electronics. This is placing the deep seabed at the center of growing commercial interest, despite the ecological risks.

As demand for these minerals rises, some mining companies, governments, and private investors view the deep ocean as a new frontier for resource extraction, a potential solution to meet mineral demand while avoiding some of the environmental and social costs of land-based mining.

For many years, deep-sea mining remained out of reach, largely due to the extreme conditions of the deep ocean. But as technology advances, these barriers are becoming easier to overcome. What was once impossible could now be technically feasible, and that makes the question of whether deep-sea mining should be permitted to proceed all the more urgent.

Why it matters: life, ecological balance, and ocean governance

The deep sea is far from a lifeless void. It is teeming with extraordinary lifeforms uniquely adapted to crushing pressures, frigid temperatures, and complete darkness. Many of these organisms are found nowhere else on Earth. These species are not only biologically remarkable, but they are also ecologically essential, with some forming the foundation of food webs that support entire ecosystems both in the ocean and on land.

The deep sea also plays a critical role in regulating our planet’s ability to host life. Its cycles, physical, chemical and biological, are essential to produce oxygen, water and nitrogen, or store carbon and atmospheric heat. Disturbing these processes at scale could release stored carbon, accelerate ocean acidification, and disrupt ecological balance in ways we cannot yet understand.

Remarkably, recent research has suggested that a process linked to polymetallic nodules may produce oxygen without sunlight, a phenomenon dubbed “dark oxygen”2. If confirmed, this would reveal a previously unknown pathway for oxygen generation, possibly transforming our understanding of how life on Earth began, and further underscoring the value of these ecosystems.

Beyond the environmental, other concerns include shared governance and economic benefit sharing. The deep sea beyond national jurisdiction is considered the common heritage of humankind, a shared space meant to benefit all nations and peoples. Yet, the financial benefits of deep-sea mining are likely to be captured by a small number of economically advanced private companies and nations, while the environmental costs will be borne by all. This may be felt most acutely by the small island states and coastal communities who rely on a healthy ocean for food security, livelihoods, and cultural identity.

A high-risk gamble with uncertain gains

In this context, it’s important to consider what is the true balance between costs and benefits, and who will bear the consequences?

Proponents of deep-sea mining argue that it is essential to meet future demand for minerals, with some even claiming it will reduce the human and environmental impacts of terrestrial mining.

But these claims do not hold up under scrutiny.

Firstly, there is already an oversupply of many of the raw minerals involved (though processing of those metals is limiting availability) and alternatives already exist. Last year terrestrial mines even closed due to low prices and a glut of some metals. Technologies for battery recycling, metal substitution, and more efficient mineral use are advancing rapidly. Some companies are now developing next-generation batteries, such as sodium-ion batteries, that use abundant and widely available materials. A transition to a more circular economy can also significantly reduce the demand for raw materials, whether from land or sea.

Secondly, the environmental risks are as great as, if not worse than those from terrestrial mines. With the current technology, a single 30-year mining contract could strip a seabed surface about a third the area of Belgium, likely generating sediment plumes that could smother an even larger area. Noise and vibrations would disrupt marine life over long distances impacting important fisheries. The destruction of habitats, including those of species that science has not even discovered let alone named, would be irreversible.

Lastly, the economic case for deep-sea mining is fragile and clouded by uncertainty. Research we have supported suggests this is a financially precarious venture due to high capital and operational costs, market uncertainty, and potential environmental liabilities3.

While the projected benefits remain speculative, more recent analysis has quantified the risks, pointing to a 13% increase in environmental risks, 8–11% in social risks, and an 11% rise in economic risks4. These findings raise a fundamental question: can we justify the likely harm in pursuit of uncertain rewards?

📷Schmidt Ocean Institute

A moratorium for a pause with purpose

The mineral resources on the seabed beyond national jurisdiction are overseen by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), a UN body tasked with protecting marine biodiversity and regulating seabed mining for the benefit of all humankind. But in 2021, a legal trigger known as the “two-year rule” accelerated pressure to finalize mining regulations, even in the absence of robust environmental safeguards. That deadline expired in July 2023, leaving legal and political challenges.

At the same time, some countries are making unilateral moves to advance mining interests, bypassing multilateral consensus and the precautionary approach that has long been the basis of ocean governance even by those who aren’t ISA members. These actions risk undermining international cooperation at a time when the world has committed to protecting 30% of the planet by 2030 and halting biodiversity loss.

In this context, a global moratorium on deep-sea mining is logical, responsible, and according to some legal experts, an obligation. A moratorium would give the international community the time and space to conduct independent scientific assessments of potential impacts, develop transparent, inclusive governance frameworks, and accelerate alternatives such as recycling, substitution, and sustainable resource use.

Over 20 countries, including France, Fiji, Chile, and Vanuatu, have already called for a pause. So have hundreds of scientists, major financial institutions, and global companies like Google, BMW, and Samsung. Just last week, New Caledonia boldly adopted a 50-year ban on deep-sea mining across its entire maritime zone.

With the ocean already under pressure from biodiversity loss, overfishing, rising temperatures, and pollution, we cannot afford to open a new chapter of irreversible harm, especially in a place we are only beginning to understand. In these depths, life evolves slowly. Some species live for centuries. Disturb them, and they may never return.

We are the first generation to glimpse the wonders of the deep, and perhaps the last with the chance to leave it intact.

I stand for a moratorium. I stand for science. I stand for the ocean. And I hope you will stand with me, before it’s too late to turn back.

Resources

🧭Learn more: https://deep-sea-conservation.org/

🪸Immerse yourself: https://deeprising.com/documentary/

⚓Get involved: https://defendthedeep.org/

Sources

1. Levin, L. A. et al. (2020). “Deep-Sea Biodiversity and Ecosystems: A Scoping Review of Threats, Impacts, and Knowledge Gaps.” Frontiers in Marine Science, 7: 384. DOI: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00384

2. Sweetman, A.K., Smith, A.J., de Jonge, D.S.W. et al. Evidence of dark oxygen production at the abyssal seafloor. Nat. Geosci. 17, 737–739 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01480-8

3. Niner, H. J., Ardron, J. A., Escobar, E. G., Gianni, M., Jaeckel, A. L., Jones, D. O. B., … & Sumaila, U. R. (2021). Deep-sea mining with no net loss of biodiversity—An impossible aim. Frontiers in Marine Science, 8, 571591. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.571591

4. Alam L, Pradhoshini KP, Flint RA, Sumaila UR (2025) Deep-sea mining and its risks for social-ecological systems: Insights from simulation-based analyses. PLoS ONE 20(3): e0320888. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0320888